Regulation of Autonomous AI Systems: Upcoming EU/US Policy Directions

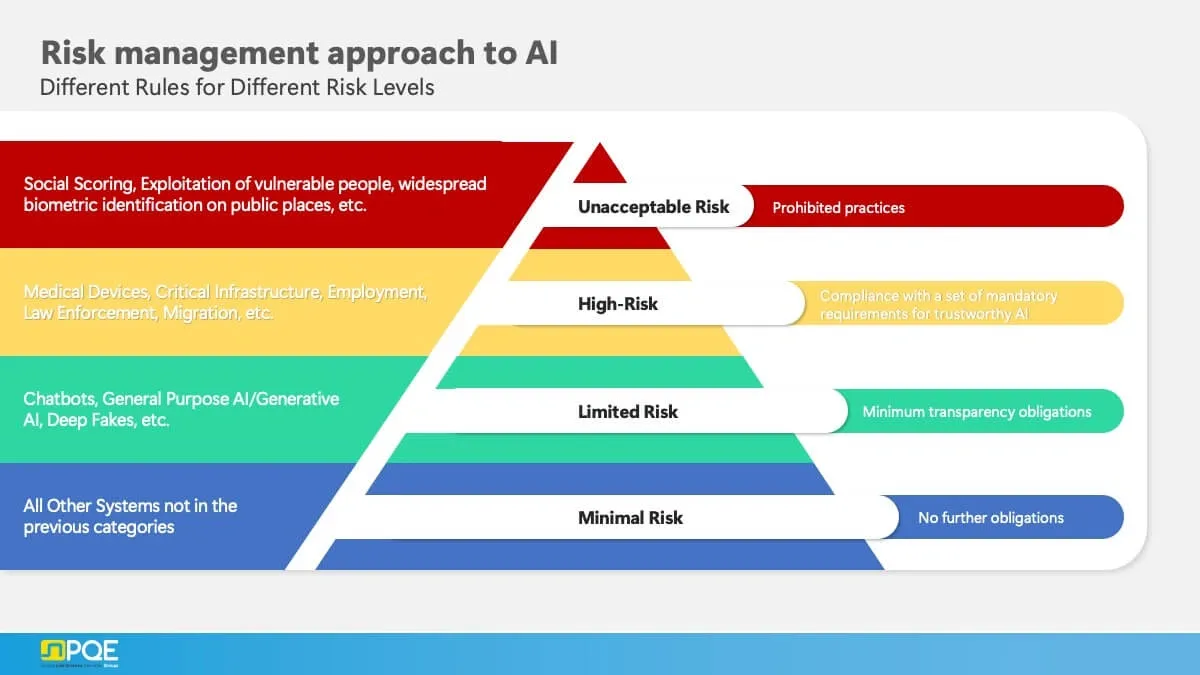

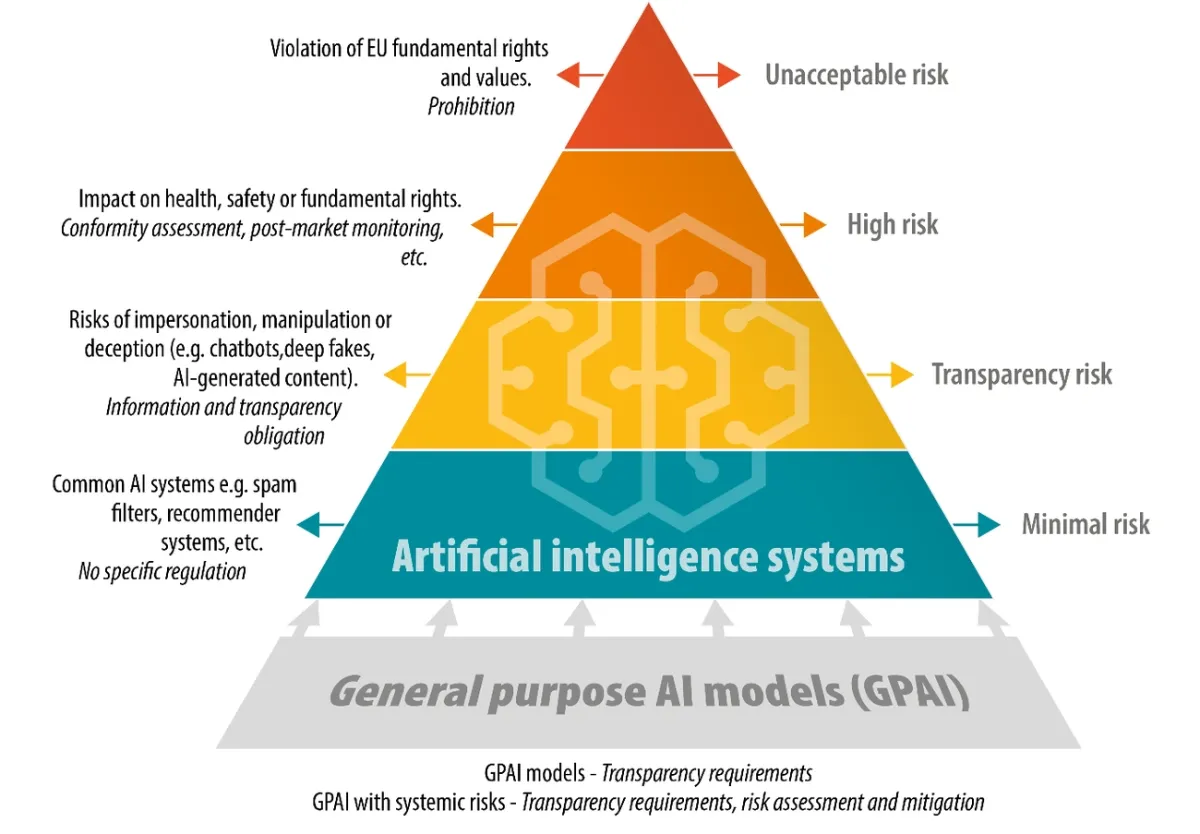

The EU’s Artificial Intelligence Act represents the world’s first detailed AI law that creates new regulatory frameworks for AI systems. This groundbreaking legislation will take effect on August 1, 2024. The law introduces a risk-based system that puts AI applications into four categories: unacceptable risk, high risk, limited risk, and minimal or no risk.

The act completely bans systems with unacceptable risks. These include cognitive behavioral manipulation, social scoring AI, and up-to-the-minute biometric identification systems. On top of that, high-risk AI applications must meet strict compliance requirements. This applies to socioeconomic processes, government use, and regulated consumer products with AI components. The European Commission holds authority to issue delegated acts and guidelines, while the governance structure operates at the EU level. The law’s effects will likely shape global standards, as with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Both the EU and US agree on risk-based approaches and trustworthy AI principles. However, their AI laws and regulations show different policy directions that will influence AI development worldwide.

Risk-Based Classification of Autonomous AI Systems

The EU Artificial Intelligence Act uses a tiered risk-based system that groups AI applications based on their effects on health, safety, and fundamental rights. This system sets clear limits for autonomous AI systems and balances new ideas with protection.

Prohibited AI Use Cases: Social Scoring, Biometric Surveillance

The EU artificial intelligence law bans several AI practices that pose unacceptable risks to society. These banned applications include social scoring systems that review people based on their social behavior or personal traits. This could lead to unfair treatment in situations unrelated to the original data collection. Social scoring AI puts people into categories based on their behavior, socioeconomic status, or personal characteristics.

Biometric identification systems must follow strict rules. The law bans AI systems that build or grow facial recognition databases by scraping facial images from the internet or CCTV footage. Real-time remote biometric identification in public spaces for law enforcement is not allowed, except in specific cases like finding kidnapping victims, stopping terrorist attacks, or tracking serious crime suspects.

The act bans AI systems that detect emotions at work and in schools, unless needed for medical or safety reasons. The law also stops biometric systems that try to figure out sensitive details like race, political views, religious beliefs, or sexual orientation from biometric data.

High-Risk AI in Education, Employment, and Law Enforcement

High-risk AI systems need to meet strict requirements but aren’t completely banned. Educational AI tools that control access to schools, check learning results, or watch students during tests are considered high-risk. These tools can shape a person’s educational and professional future.

AI systems in employment face similar scrutiny. Tools that handle recruitment, including those that show targeted job ads, look through applications, check candidates, or make decisions about promotions and firing, are labeled high-risk. These systems could affect workers’ future careers and income.

Law enforcement AI labeled as high-risk includes systems that predict crime victimization or offending, lie detector tools, and AI that checks evidence reliability in criminal cases. These systems must be accurate, robust, and fair while using proper documentation, records, risk management, and human oversight.

Limited-Risk AI: Chatbots and Deepfakes Disclosure

Between high-risk and minimal risk lies a category of limited-risk AI systems that must be transparent. Chatbots and digital assistants must tell users they’re not human. Users should know when they talk to machines instead of people.

The EU artificial intelligence act requires generative AI systems to mark their synthetic audio, images, videos, or text in a way machines can read and detect. Deepfakes—AI content that looks like real people or events—must come with clear labels showing they’re artificial.

Text generators that inform the public about important matters must reveal they’re artificial, except for law enforcement or when humans review the content with editorial responsibility. Political parties promised not to use deepfakes in their campaigns before the European elections in April 2024. This shows how artificial intelligence law shapes political discussions.

Limited-risk AI transparency rules show a balanced approach in artificial intelligence act regulations. They address potential risks without putting up barriers that might slow down helpful innovations.

General Purpose AI Models and Systemic Risk

The EU’s regulatory framework addresses advanced AI technologies through specific rules for General Purpose AI (GPAI) models in the AI Act. These adaptable systems need their own regulatory approach that goes beyond standard risk classifications.

Definition of GPAI under Article 3(66)

Article 3(63) of the EU artificial intelligence act defines a General-Purpose AI model as “an AI model that displays significant generality and is capable of competently performing a wide range of distinct tasks whatever the way the model is placed on the market and that can be integrated into a variety of downstream systems or applications”. Models trained with extensive data using self-supervision at scale fall under this definition.

Article 3(66) provides another definition for General-Purpose AI systems. These systems are “an AI system which is based on a general-purpose AI model and which has the capability to serve a variety of purposes, both for direct use as well as for integration in other AI systems”. Large language models that can handle various tasks in different domains are part of this category.

Models that use more than 10^23 floating point operations (FLOPs) to generate language, text-to-image, or text-to-video content are typically considered GPAI models. This usually means models with about one billion parameters trained on large datasets.

FLOPs Threshold and Systemic Risk Criteria

The artificial intelligence law introduces “systemic risk” for advanced models. Article 3(65) states that systemic risk is “a risk that is specific to the high-impact capabilities of general-purpose AI models, having a most important affect on the Union market due to their reach, or due to actual or reasonably foreseeable negative effects on public health, safety, public security, fundamental rights, or the society as a whole”.

The EU artificial intelligence act sets a computational threshold of 10^25 FLOPs used for training to identify such models. This massive processing requirement costs tens of millions of Euros and indicates high-impact capabilities. GPT-4, Gemini Ultra, and Llama 3 are notable models that exceed this threshold.

Developers must alert the European Commission within two weeks if their models reach or might reach this threshold. Notwithstanding that, providers can challenge this classification with solid evidence showing their model lacks systemic risk. Their obligations stay in place during the review.

Models with systemic risk must meet additional requirements:

- Risk assessments throughout the model’s lifecycle must be complete

- State-of-the-art model evaluations with adversarial testing are necessary

- Serious incidents need reporting to authorities

- Strong risk mitigation measures must be in place

- Resilient infrastructure for cybersecurity protection is essential

Code of Practice for GPAI Providers

The EU artificial intelligence act created a voluntary Code of Practice that helps GPAI providers show compliance. The Commission and AI Board endorsed this Code on July 10, 2025 as an adequate voluntary tool.

The Code has three main chapters: Transparency, Copyright, and Safety/Security. The first two chapters apply to all GPAI model providers. These chapters cover Article 53 requirements about technical documentation, information accessibility, copyright compliance, and training content disclosure.

GPAI model providers with systemic risk must follow the Safety and Security chapter. This section outlines practical state-of-the-art methods to manage what it all means. Providers who sign must create a resilient Safety and Security Framework before releasing their model. They need to identify risks through well-laid-out processes and submit detailed Safety and Security Model Reports.

The Code remains voluntary, but signing it reduces administrative work and provides more legal certainty than other compliance methods. Providers who skip signing might face more regulatory questions. They might also need to show how their compliance frameworks compare to the Code’s measures.

The AI Office watches technological developments to keep classification thresholds current. The Commission can update these thresholds through delegated acts as technology advances.

Governance Structures in EU and US AI Law

The governance frameworks for AI law show clear differences between EU’s centralized structures and US’s decentralized approaches. These differences highlight contrasting regulatory philosophies.

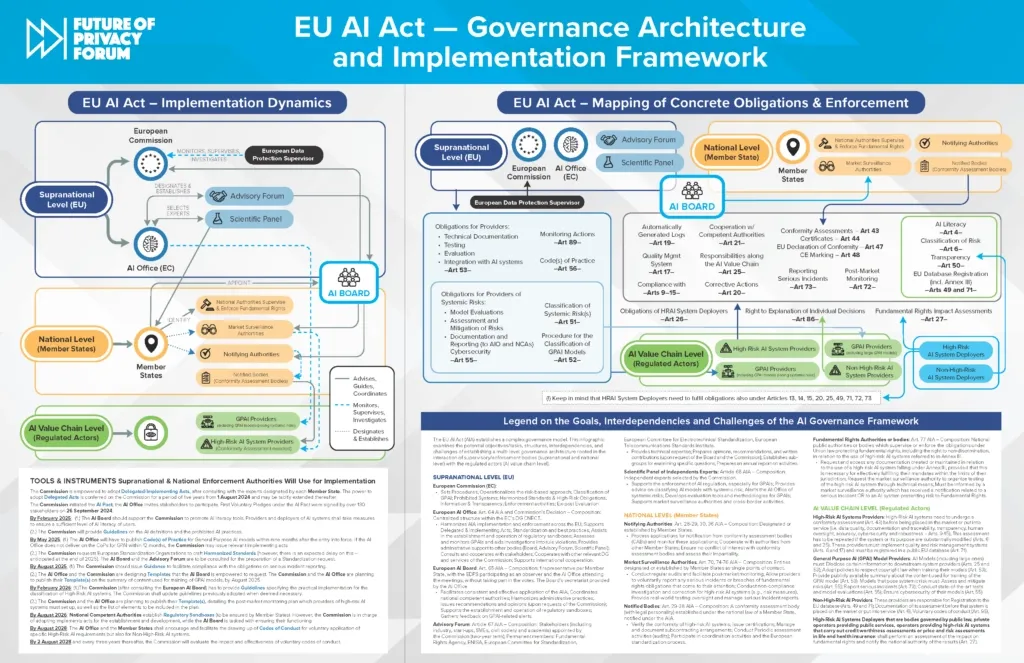

Role of the EU AI Office and AI Board

The EU AI Office acts as the central coordination body in the European Union’s governance structure for AI law implementation. The AI Act created this office within the European Commission. It has exclusive powers to supervise providers of General Purpose AI models. The office’s authority lets it request information, conduct evaluations, and impose compliance measures. These measures include risk mitigation or model withdrawal when needed. The office helps apply the EU artificial intelligence act consistently across Member States. It supports information exchange and serves as the AI Board’s secretariat.

The European Artificial Intelligence Board is the life-blood of EU governance with representatives from each Member State. A Member State chairs the board that coordinates national authorities responsible for enforcement. The board gathers technical expertise and shares regulatory best practices. It functions as an advisory body to ensure uniform AI law implementation throughout the Union. The European Data Protection Supervisor and EEA-EFTA countries join board meetings as observers, adding a broader viewpoint to its oversight.

US Federal Agencies and Sectoral Oversight

In stark comparison to this unified EU framework, the United States uses a fragmented approach to AI governance. It relies on existing federal agencies that operate under legacy laws without a central AI regulator. This decentralized structure shows the complex US regulatory environment for AI laws and regulations.

Executive Order 14110 from October 2023 assigned over 50 federal entities to develop policies in eight key areas. These areas cover algorithmic bias mitigation, AI safety, innovation, worker support, consumer protection, privacy, federal AI use, and international leadership. A White House Artificial Intelligence Council with 28 federal departments and agencies coordinates implementation.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) created an AI accountability framework based on four principles: governance, data quality, performance monitoring, and results evaluation. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) leads AI investigations despite limited tools. It uses existing authority to regulate AI systems. This sectoral oversight has led to inconsistent enforcement priorities across jurisdictions. States often fill these regulatory gaps.

Scientific Panel and Advisory Forum in the EU

The EU strengthened its governance model with two advisory bodies. The Scientific Panel of independent experts connects with the academic community. It gives explanations about AI’s evolving landscape impartially. The panel offers scientific and technical advice on critical issues like AI system classification, risk assessment, and evaluation methods.

The Advisory Forum works as a general advisory body to the Commission and complements the Scientific Panel’s work with stakeholder input. The forum’s membership balances representatives from industry, start-ups, SMEs, civil society, and academia. This balance ensures equal representation of commercial and non-commercial interests. Key EU agencies serve as permanent members, including the Fundamental Rights Agency, ENISA, and standardization bodies like CEN, CENELEC, and ETSI. Members serve two-year terms that can be renewed once. They take part in meetings, subgroups, and written contributions actively.

The EU artificial intelligence act creates a detailed framework for oversight through this layered governance structure. Meanwhile, US artificial intelligence law depends on distributed authority across existing regulatory bodies. These approaches show fundamental differences in regulating autonomous AI systems.

Compliance, Liability, and Enforcement Mechanisms

Compliance mechanisms are the foundations of artificial intelligence law enforcement. They create vital guidelines for safety verification, liability determination, and information disclosure in regulated systems.

Conformity Assessments and CE Marking in the EU

The EU artificial intelligence act requires assessment procedures for high-risk AI systems before market placement. Providers can choose between internal control assessment or third-party evaluation by Notified Bodies based on standard adherence. Internal assessments need quality management system verification, technical documentation review, and consistency checks with post-market monitoring systems. External evaluations become mandatory for remote biometric identification systems or systems that make inferences from biometric data.

High-risk AI systems must display the CE marking after successful assessment. This visual indicator shows compliance with safety standards. Digital AI systems must make this marking available through the interface or machine-readable code. Physical systems need visible, legible, and permanent markings. When impractical, markings can appear on packaging or documentation. The Notified Body’s identification number must appear with the CE marking in promotional materials.

Product Liability Directive and AI Liability Directive

Two complementary instruments address AI-related harms today. The revised Product Liability Directive now includes software and AI systems. It establishes strict liability for defective products that cause damage. The directive assumes defectiveness when manufacturers don’t disclose relevant evidence, products violate safety requirements, or obvious malfunctions happen during normal use.

The AI Liability Directive deals with non-contractual fault-based claims. It creates a “presumption of causality” to help victims prove their cases. National courts can order evidence disclosure about high-risk AI systems suspected of causing damage. This proves especially useful since AI’s complexity makes establishing causation challenging. This framework ensures AI system victims receive the same protection as those harmed by other technologies.

Whistleblower Protections and Audit Trails

Resilient whistleblower protections are a vital yet minimal component of AI oversight. The bipartisan AI Whistleblower Protection Act in the US protects disclosures about “substantial and specific dangers” to public safety or security vulnerabilities. These protections apply even without law violations. The Act makes contractual waivers of whistleblower rights unenforceable, which nullifies broad NDAs.

The EU Whistleblowing Directive will cover AI Act violations starting August 2026. It protects individuals in professional relationships under EU law. Until then, whistleblowers can still receive protection when reporting AI concerns under existing categories like product safety or data protection.

Detailed audit trails for high-risk AI systems enable accountability. They provide secure, time-stamped records of system activity that support transparency, traceability, and legal responsibility for AI decisions.

Challenges in Cross-Border AI Regulation

Different countries follow their own rules for AI systems. This creates major challenges for global AI deployment and compliance as nations take different approaches to legislation.

Fragmentation in US State-Level AI Laws

The United States lacks the EU’s unified approach and faces a complex regulatory landscape at the state level. State legislators proposed more than 1,100 AI-related bills in 2025 alone. Colorado led the way with complete risk-based AI laws, but California took a different path. After their complete bill failed, California passed several targeted laws about election deepfakes and AI-generated content warnings. Companies that work nationwide must follow the strictest state requirements across all their operations. This creates huge problems for businesses. Small companies struggle the most, and California’s rules could cost them up to £12,706.56 each year. This “interstate innovation tax” puts both small business growth and America’s tech leadership at risk.

Extraterritorial Impact of EU Artificial Intelligence Law

The EU AI Act reaches way beyond European borders. Non-EU organizations must follow these rules if their AI systems or outputs are used in the EU, even without a physical presence there. Article 2 makes this clear – the Act applies to anyone putting AI systems in the EU market and to users in other countries whose AI outputs end up in the Union. So, companies outside the EU might need representatives within Europe and must line up their development with European standards. The EU rules could become the world’s default standard, but this creates real headaches for companies working in multiple regions.

Interoperability of AI Standards and APIs

The global AI governance landscape looks like a scattered puzzle of rules, technical standards, and frameworks. Most systems stay trapped within company walls because there’s no standard way for AI systems to talk to each other. Companies face big problems when they try to use multiple AI tools from different vendors. Data formats don’t match up and integration becomes difficult. Each new AI platform speaks its own “language” with unique data formats, APIs, and operating rules. These differences cause real-life problems – shipments go wrong, inventory gets mixed up, and customer service suffers. The challenges go beyond technical issues. Companies also struggle with trust, security, and costs as they try to keep track of how their various AI tools work together.

Future Policy Directions and Regulatory Innovation

New policy mechanisms are taking shape worldwide to adapt AI laws and regulations to fast-changing technologies. These mechanisms balance breakthroughs with strong safety standards.

AI Regulatory Sandboxes in EU Member States

Regulatory sandboxes provide controlled environments where companies can develop and test AI systems under official guidance before market launch. Each EU Member State must set up at least one AI regulatory sandbox by August 2, 2026. These environments boost legal certainty, help with compliance, and aid market access for SMEs and startups. Companies can prove their compliance with the EU artificial intelligence act through sandbox participation. Providers who follow sandbox guidelines also avoid administrative fines. Success stories from other sectors show that companies completing sandbox testing attracted 6.6 times more investment than their competitors.

US National AI Research Resource (NAIRR)

NAIRR’s program tackles the problem of unequal access to AI resources among researchers. This pilot program launched in January 2024 connects researchers to:

- Computational infrastructure

- AI-ready datasets

- Pre-trained models

- Software tools

The program builds on partnerships with 13 federal agencies and 28 non-governmental contributors. Though it received over 150 proposals, budget limits meant only 35 projects got funding.

AI Literacy and Workforce Transition Programs

The workforce of 2035 presents a unique challenge – 71% of its members are already hired. FutureDotNow’s report highlights four essential AI skills every worker needs: foundational AI literacy, effective AI interaction, critical evaluation, and ethical use. The UK economy could see an annual boost of £23 billion by developing these skills.

Conclusion

AI regulatory systems worldwide are at a turning point as different regions take their own paths to governance. Our analysis shows how the EU Artificial Intelligence Act creates a complete risk-based system that groups AI applications by their potential harm. This groundbreaking law bans high-risk systems and places graduated requirements on other risk levels.

The governance structures show deep philosophical gaps between regions. The EU has built a central system where the AI Office and AI Board provide unified oversight. The United States takes a different route by using existing agencies and sector-specific rules. These differences reflect each region’s core values and priorities.

General Purpose AI models get special attention under EU rules. Systems above certain computing power must follow strict rules to manage system-wide risks. A voluntary Code of Practice offers a way to comply, but providers must assess and reduce risks whatever their participation level.

Cross-border implementation brings its own set of problems. US state-level rules create extra work, especially for smaller companies working across states. EU regulations reach beyond borders and affect global AI practices even for companies with no European presence.

Regulatory innovation moves forward through tools like AI sandboxes that let companies test new systems safely. The US National AI Research Resource tackles unequal access to infrastructure. Programs help workers adapt to technological shifts.

Technical standards remain a tough challenge. Different AI systems don’t work well together, which makes platform integration difficult and slows down effective governance. Policymakers need to balance innovation with safety as autonomous AI becomes more central to society.

AI regulation will reshape the scene for decades to come. These first comprehensive AI laws set key precedents, but rules must adapt as technology grows and new capabilities surface. Smart organizations see good governance not as a limit but as a way to build public trust and ensure eco-friendly AI use.

FAQs

Q1. What is the EU’s approach to regulating AI systems? The EU has adopted a risk-based approach in its Artificial Intelligence Act, categorizing AI systems into four risk levels: unacceptable, high, limited, and minimal. This framework bans unacceptable risk systems, imposes strict requirements on high-risk applications, and sets transparency obligations for limited-risk AI.

Q2. How does the EU define and regulate General Purpose AI models? The EU defines General Purpose AI models as those displaying significant generality and capable of performing a wide range of tasks. Models trained using more than 10^25 FLOPs are considered to have potential systemic risk and face additional obligations, including comprehensive risk assessments and cybersecurity measures.

Q3. What are the key differences between EU and US AI governance structures? The EU has established a centralized governance structure with the EU AI Office and AI Board, while the US relies on existing federal agencies and sectoral oversight. This reflects fundamental differences in regulatory philosophy, with the EU adopting a unified approach and the US maintaining a more fragmented system.

Q4. How does the EU AI Act address liability for AI-related harms? The EU has introduced two complementary instruments: the revised Product Liability Directive, which extends coverage to AI systems, and the AI Liability Directive, which focuses on non-contractual fault-based claims. These aim to ensure equivalent protection for persons harmed by AI systems as those harmed by other technologies.

Q5. What challenges exist in cross-border AI regulation? Cross-border AI regulation faces challenges such as fragmentation of US state-level AI laws, the extraterritorial impact of EU regulations, and the lack of interoperability in AI standards and APIs. These issues create compliance burdens for companies operating across multiple jurisdictions and hinder effective global AI governance.

Leave a Reply